*The Legislative Councils in British West Africa should have half i.e. 50% of its membership directly elected,

*There should be a West Africa House of Assembly made up of all the members of the Legislative Councils plus six (6) financial representatives elected by the people to control revenue and expenditure.

*Municipal Councils dominated by Africans should be established,

*The Civil Service should be Africanised.

*Syrian and Lebanese traders should be expelled,

*The right of the installation or deposition of chiefs should continue to be in the hands of the people, vii) A West African University should be established, viii) A Law making education compulsory be enacted and that the standard of primary and secondary education should be raised.

With these demands, in September 1920 the Congress dispatched a deputation to London. It consisted of Chief Oluwa and J. Egerton Shyngle from Nigeria, T. Hutton Mills, H. Van Hein and J. E. Casely-Hayford from Ghana, Dr. H.C. Bankole-Bright and F.W. Dove from Sierra Leone, and E.F. Small and H, M. Jones from The Gambia. Though the deputation remained in London until January 1921, not only were all their demands for constitutional and judicial reforms rejected, but Lord Milner, the Colonial Secretary, refused to grant them audience.

Despite this fiasco, it was owing to the pressure mounted by the Congress that the Colonial Administration introduced limited constitutional reforms. The principle of elective representation was for the first time introduced into the 1922 Constitution of Nigeria, the 1924 Constitution of Sierra Leone and the 1925 Constitution of Ghana. The Congress was the first practical attempt of pan-Africanism, which sought to unite the African elite to fight for a common cause.

Amodu Tijani, Chief Oluwa of Lagos. Circa 12 July 1920. © National Portrait Gallery, London

Highly unashamed of his strong nationalist views and not fearful nor a stooge of the British colonial administration like his forebear King Docemo of Lagos who signed away the vast native land of Lagos to the British for free, Chief Oluwa argued consistently with the British that the colonial government had no authority to interfere with the Oba's (ruler of Lagos) rule and sued the British colonial government for using legal tricks in stealing Lagos lands.

When he lost the case at the Lagos high court, in 1920 Oluwa and great Nigerian nationalist, Herbert Macaulay, who was then serving as Oluwa`s secretary and interpreter visited the Privy Council in London to defend the Oba's right of ownership to land the colonial government had appropriated. The Council ruled in their favour. This case proved to be a landmark in Nigerian history as it recognised the Chiefs as absolute owners of the land. Songs and poems were later composed in Oluwa's honour.

In his recent 2013 book entitled "Imperial Justice: Africans in Empire's Court" Bonny Ibhawoh writes that "The British imperial justice reached a milestone in 1921. In that year the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC), the final Court of Appeal for all legal disputes throughout the British Empire, passed a landmark case (the Amadu Tijani case) that was to reverberate across the empire because of the precedent it set on the question of Indigenous land right. The appeal was brought to the Privy Council by an African Chief, Chief Oluwa, against the Colonial government in Nigeria demanding compensation for the "illegal" expropriation of his ancestral land. At the heart of the matter was the Treaty of Cession signed between Britain and one of the Chief Oluwa`s forebearer, King Docemo, in 1861. The colonial government claimed that, under the terms of that treaty, the British Crown has acquired ownership of all lands in the colony of Lagos, including lands claimed by Chief Oluwa. Indeed, the 1861 states that King Docemo agreed to transfer to the Queen of Great Britain, "her heirs and successors forever," the land of Lagos, "freely, fully, entirely, and absolutely."

Chief Amodu Tijani, the Oluwa Of Lagos ( Standing Left) ,During Ramadan Celebration

The key question was whether Chief Oluwa (Amadu Tijani) was entitled to compensation under the provisions of the Public Lands Ordinance of 1903 which permitted compulsory acquisition of lands but requires compensations to be paid to all persons with interest in the land. At the end of the protracted case, the PC ruled that, as the trustee of his native community, Chief Oluwa was entitled to be compensated for the land expropriated by the government. Whatever concession his forebears may have made to the British Crown was was made under the assumption that the property rights of the inhabitants were to be fully respected. The simple assertion of the British authority, and could not, serve to extinguish the legal rights of the aboriginal people to their traditional territories. Although this was a long established colonial principle applied where the indigenous peoples were in occupation of the land and using it, the ruling by the highest court in the Empire was significant. With this ruling, there was no more doubt that primary ownership of Lagos lands rested not with the British Crown, but with the indigenous inhabitants of Lagos.

Beyond its legal import, the PC`s decision in the Amadu Tijani case had great political and symbolic significance for many Africans. One local newspaper editorialized that the victory was a "boon for all West Africans," proclaiming: "Today, the dictum that `the white men Government make no mistake' has been exploded and proved to be erroneous and untrue." The news of the decision occasioned two weeks of celebrations and festivities in the streets of Lagos. On his return journey from London, where he had gone to witness the case, Chief Oluwa received congratulatory messages from African leaders and learned elites at every port of call on the West African coast, from Freetown in Sierra Leone to Sekondi and Accra in the Gold Coast. Forty thousand people turned out to at a ceremony to welcome victorious Chief Oluwa and his entourage when they arrived on the Lagos shore on the morning of 25th August 1921.

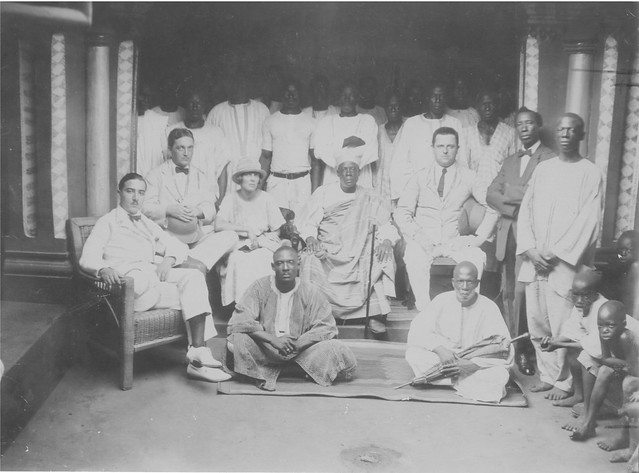

Chief Oluwa receives members of the Dutch colony (Lagos, Nigeria, 1922)

The Judicial Committee

His Majesty's Privy Council

Monday, the 11th day of July 1921

Before a Board of

Viscount Haldane

Lord Atkinson

Lord Phillimore

Between

Amodu Tijani

.......

Appellant

And

The Secretary, Southern Provinces

.......

Respondent

Judgment of the Court

Delivered by

Viscount Haldane

In this case the question raised is as to the basis for calculation of the compensation payable to the appellant, who claims for the taking by the Government of the Colony of Southern Nigeria of certain land for public purpose. There was a preliminary point as to whether the terms of the Public Lands Ordinance of the Colony do not make the decision of its Supreme Court on such a question final. As to this it is sufficient to say that the terms of the Ordinance did not preclude the exercise which has been made of the Prerogative of the Crown to give special leave to bring this appeal.

The Public Lands Ordinance of 1903 of the Colony provides that the Governor may take any lands required for public purposes for an estate in fee simple or for a less estate, on paying compensation to be agreed on or determined by the Supreme Court of the Colony. The Governor is to give notice to all the persons interested in the land, or to the persons authorised by the Ordinance to sell. and convey it. Where the land required is the property of a native community, the Head Chief of the community may sell and convey it in fee simple, any native law or custom to the contrary notwithstanding. There is to be no compensation for land unoccupied unless it is proved that, for at least six months during the ten years preceding any notice, certain kinds of beneficial use have been made of it. In other cases the Court is to assess the compensation according to the value at the time when the notice was served, inclusive of damage done by severance. Prima facie, the persons in possession, as if owners, are to be deemed entitled. Generally speaking, the Governor may pay the compensation in accordance with the direction of the Court, but where any consideration or compensation is paid to a Head Chief in respect of any land, the property of a native community, such consideration or compensation is to be distributed by him among the members of the community or applied or used for their benefit in such proportions and manner as the Native Council of the District in which the land is situated, determines with the sanction of the Governor.

The land in question is at Apapa, on the mainland and within the Colony. The appellant is the Head Chief of the Oluwa family or community, and is one of the Idejos or landowning white cap chiefs of Lagos and the land is occupied by persons some of whom pay rent or tribute to him. Apart from any family or private land which the Chief may possess or may have allotted to members of his own family, he has in a representative or official capacity control by custom over the tracts within his Chieftaincy, including, as Chief Justice Speed points out in his judgment in this case, power of allotment and of exacting a small tribute or rent in acknowledgment of his position as Head. But when in the present proceedings he claimed for the whole value of the land in question, as being land which he was empowered by the Ordinance to sell, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court held that, although he had a right which must be recognised and paid for, this right was:

" merely a seigneurial right giving the holder ordinary rights of control and management of the land in accordance with the well-known principles of native law and custom, including the right to receive payment of the nominal rent or tribute payable by the occupiers, and that compensation should be calculated on that basis, and not on the basis of absolute ownership of the land."

It does not appear clearly from the judgment of the Chief Justice whether he thought that the members of the community had any independent right to compensation, or whether the Crown was entitled to appropriate the land without more.

The appellant, on the other hand, contended that, although his claim was, as appears from the statement of his advocate, restricted to one in a representative capacity, it extended to the full value of the family properly and community land vested in him as Chief, for the latter of which he claimed to be entitled to be dealt with under the terms of the Ordinance in the capacity of representing his community and its full title of occupation.

The question which their Lordships have to decide is which of these views is the true one. In order to answer the question, it is necessary to consider, in the first place the real character of the native title to the land.

Their Lordships make the preliminary observation that in interpreting the native title to land, not only in Southern Nigeria, but other parts of the British Empire, much caution is essential. There is a tendency, operating at times unconsciously, to render that title conceptually in terms which are appropriate only to systems which have grown up under English law. But this tendency has to be held in check closely. As a rule, in the various systems of native jurisprudence throughout the Empire, there is no such full division between property and possession as English lawyers are familiar with. A very usual form of native title is that of a usufructuary right, which is a mere qualification of or burden on the radical or final title of the Sovereign where that exists. In such cases the title of the Sovereign is a pure legal estate, to which beneficial rights mayor may not be attached. But this estate is qualified by a right of beneficial user which may not assume definite forms analogous to estates, or may, where it has assumed these, have derived them from the intrusion of the mere analogy of English jurisprudence. Their Lordships have elsewhere explained principles of this kind in connection with the Indian title to reserve lands in Canada. But the Indian title in Canada affords by no means the only illustration of the necessity for getting rid of the assumption that the ownership of land naturally breaks itself up into estates, conceived as creatures of inherent legal principle. Even where an estate in fee is definitely recognised as the most comprehensive estate in land which the law recognises, it does not follow that outside England it admits of being broken up. In Scotland a life estate imports no freehold title, but is simply, in contemplation of Scottish law, a burden on a right of full property that cannot be split up. In India much the same principle applies. The division of the fee into successive and independent incorporeal rights of property conceived as existing separately from the possession, is unknown. In India, as in Southern Nigeria, there is yet another feature of the fundamental nature of the title to land which must be borne in mind. The title, such as it is may not be that of the individual, as in this country it nearly always is in some form, but may be that of a community. Such a community may have the possessory title to the common enjoyment of a usufruct, with customs under which its individual members are admitted to enjoyment, and even to a right of transmitting the individual enjoyment as members by assignment inter vivos or by succession. To ascertain how far this latter development of right has progressed involves the study of the history of the particular community and its usages in each case. Abstract principles fashioned a priori are of but little assistance, and are as often as not misleading.

In the case of Lagos and the territory round it, the necessity of adopting this method of inquiry is evident. As the result of cession to the British Crown by former potentates, the radical title is now in the British Sovereign. But that title is throughout qualified by the usufructuary rights of communities, rights which, as the outcome of deliberate policy, have been respected and recognised. Even when machinery has been established for defining as far as is possible the rights of individuals by introducing Crown grants as evidence of title, such machinery has apparently not been directed to the modification of substantive rights, but rather to the definition of those already in existence and to the preservation of records of that existence.

In the instance of Lagos the character of the tenure of the land among the native communities is described by Chief Justice Rayner in the Report on Land Tenure in West Africa, which that learned Judge made in 1898, in language which their Lordships think is substantially borne out by the preponderance of authority.

" The next fact which it is important to bear in mind in order to understand the native land law is that the notion of individual ownership is quite foreign to native ideas. Land belongs to the community, the village or the family, never to the individual. All the members of the community, village or, family have an equal right to the land, but in every case the Chief or Headman of the community or village, or head of the family, has charge of the land, anti in loose mode of speech is sometimes called the owner. He is to some extent in the position of a trustee, and as such holds the land for the use of the community or family. He has control of it, and any member who wants a piece of it to cultivate or build a house upon, goes to him for it. But the land so given still remains the property of the community or family. He cannot make any important disposition of the land without consulting the elders of the community or family, and their consent must in all cases be given before a grant can be made to a stranger. This is a pure native custom along the whole length of this coast, and wherever we find, as in Lagos, individual owners, this is again due to the introduction of English ideas. But the native idea still has a firm hold on the people, and in most cases, even in Lagos, land is held by the family. This is so even in cases of land purporting to be held under Crown grants and English conveyances. The original grantee may have held as an individual owner, but on his death all his family claim an interest, which is always recognised, and thus the land becomes again family land. My experience in Lagos leads me to the conclusion that except where land has been bought by the present owner there are very few natives who are individual owners of land."

Consideration of the various documents, records and decisions, which have been brought before them in the course of the argument at the Bar, has led their Lordships to the conclusion that the view expressed by Chief Justice Rayner in the language just cited is substantially the true one. They therefore interpret paragraph 6 of the Public Lands Ordinance of 1903, which says that where lands required for public purposes are the property of a native community, " the Head Chief of such community may sell and convey the same for an estate in fee simple," as meaning that the Chief may transfer the title of the community. It follows that it is for the whole of what he so transfers that compensation has to be made. This is borne out by paragraphs 25 and 26, which provide for distribution of such compensation under the direction of the Native Council of the District, with the sanction of the Governor.

The history of the relations of the Chiefs to the British Crown in Lagos and the vicinity bears out this conclusion. About the beginning of the eighteenth century the Island of Lagos was held by a Chief called Olofin. He had parcelled out the island and part of the adjoining mainland among some sixteen subordinate Chiefs, called" Whitecap" in recognition of their domination over the portions parcelled out to them. About 1790 Lagos was successfully invaded by the neighbouring Benins. They did not remain in occupation, but left a representative as ruler whose title was the " Eleko." The successive Elekos in the end became the Kings of Lagos, although for a long time they acknowledged the sovereignty of the King of the Benins, and paid tribute to him. The Benins appear to have interfered but little with the customs and arrangements in the island. About the year 1850 payment of tribute was refused, and the King of Lagos asserted his independence. At this period Lagos had become a centre of the slave trade, and this trade centre the British Government determined to suppress. A Protectorate was at first established, and a little later it was decided to take possession of the island. The then king was named Docemo. In 1861 he made a Treaty of Cession by which he ceded to the British Crown the port and island of Lagos with all the rights, profits, territories and appurtenances thereto belonging. In 1862 the ceded territories were erected into a separate British Government, with the title" Settlement of Lagos." In 1874 this became part of the Gold Coast. In 1886 Lagos was again made a separate Colony, and finally, in 1906, it became part of the Colony of Southern Nigeria.

In 1862 a debate took place in the House of Commons which is instructive as showing the interpretation by the British Government of the footing on which it had really entered. The slave trade was to be suppressed, but Docemo was not to be maltreated. He was to have a revenue settled on and secured to him. The real possessors of the land were considered to be, not the native kings, but the whitecap chiefs. The apprehension of these Chiefs that they were to be turned out had been set at rest, so it was stated. The object was to suppress the slave trade, and to introduce orderly conditions. Such, in substance, was the announcement of policy to the House of Commons by the Under Secretary for Foreign Affairs, and the contemporary despatches and records confirms it and point to its having been carried out. The Chiefs were stated, in a despatch from the then Consul, to have been satisfied that the cession would render their private property more valuable to them. No doubt there was a cession to the British Crown, along with the Sovereignty, of the radical or ultimate title to the land, in the new Colony, but this cession appears to have been made on the footing that the rights of property of the inhabitants were to be fully respected. This principle is a usual one under British policy and law when such occupations take place. The general words of the cession are construed as having related primarily to sovereign rights only. What has been stated appears to have been the view taken by the Judicial Committee in AttorneyGeneral of Southern Nigeria v. Holt (2 N.L.R. 1.; [1915] A.C., 599), a recent case reported in 1915, and their Lordships agree with that view. Where the cession passed any proprietary rights they were rights which the ceding king possessed beneficially and free from the usufructuary qualification of his title in favour of his subjects.

In the light afforded by the narrative, it is not admissible to conclude that the Crown is, generally speaking, entitled to the beneficial ownership of the land as having so p'assed to the Crown as to displace any presumptive title of the natives. In the case of Oduntan Onisiwo v. The Attorney_General of Southern Nigeria (2 N.L.R. 77), decided by the Supreme Court of the Colony in 1912, Chief Justice Osborne laid down as regards the effect of the Cession of 1861, that he was of opinion that" the ownership rights of private landowners, including the families of the Idejos, were left entirely unimpaired, and as freely exercisable after the Cession as before." In this view their Lordships concur. A mere change in sovereignty is not to be presumed as meant to disturb rights of private owners; and the general terms of a Cession are prima facie to be construed accordingly. The introduction of the system of Crown grants which was made subsequently must be regarded as having been brought about mainly, if not exclusively, for conveyancing purposes, and not with a view to altering substantive title already existing. No doubt questions of difficulty may arise in individual instances as to the effect in law of the terms of particular documents. But when the broad question is raised as to what is meant by the provision in the Public Lands Ordinance of 1903, that where the lands to be taken are the property of a native community, the Head Chief may sell and convey it, the answer must be that he is to convey a full native title of usufruct, and that adequate compensation for what is so conveyed must be awarded for distribution among the members of the community entitled, for apportionment as the Native Council of the District, with the sanction of the Governor, may determine. The Chief is only the agent through whom the transaction is to take place, and he is to be dealt with as representing not only his own but the other interests affected.

Their Lordships now turn to the judgments of Chief Justice Speed in the two Courts below. The reasons given in these judgments were in effect adopted by the Full Court, and they are conveniently stated in what was said by the Chief Justice himself, in the Court of First Instance. He defined the question raised to be " whether the Oluwa has any rights over or title to the land in question for which compensation is payable and if so upon what basis such compensation should be fixed." His answer was that the only right or title of the Chief was a " seigneurial right giving the holder the ordinary rights of control and management of land, in accordance with the well-known principles of native law and custom, including the right to receive payment of the nominal rent or tribute payable by the occupiers, and that compensation should be calculated on that basis and not on the basis of absolute ownership. " The reasons given by the Chief Justice Speed for coming to this conclusion were as follows: According to the Benin law the King is the sovereign owner of the land, and as the territory was conquered by the Benins it follows that during the conquest the King of Benin was the real owner, the control exercised by the Chiefs under his " Eleko " or representative being exercised as part of the machinery of government and not in virtue of ownership. It might be that for a considerable period prior to 1850 the control of the King of Benin had been relaxed until it became little more than a formal and nominal overlordship, and that in this period there had been a tendency on the part of the minor chiefs to arrogate to themselves powers to which constitutionally they had no claim, including independent powers of control and management. But the effect of the Cession of 1861 was that, even according to the then strict native law, all the rights over the land, including sovereign ownership, passed to the British Crown. He finds that what was recognised by the British Government was simply the title of the Chiefs to exercise a kind of control over considerable tracts of land, including the right to allot such lands to members of their family and others for the purposes of cultivation, and to receive a nominal rent or tribute as an acknowledgment of " seigneurial " right. Strict native law would not have supported this claim, but it was made and acquiesced in, although there were certain Crown grants which appear to have ignored it. There was thus no title to absolute ownership in the Chiefs, and, so far as the judgment in the Onisiwo case (already referred to), was inconsistent with this view, it was based on a confusion between family and Chieftaincy property. It was true that in yet another case in 1907, which came before the Full Court the Government had paid compensation on the basis of absolute ownership, but in that case the Government had not raised the question of title, and the decision consequently could not be regarded as authoritative.

Their Lordships think that the learned Chief Justice in the judgment thus summarised, which virtually excludes the legal reality of the community usufruct, has failed to recognise the real character of the title to land occupied by a native community. That title, as they have pointed out, is prima jacie based, not on such individual ownership as English law has made familiar, but on a communal usufructuary occupation, which may be so complete as to reduce any radical right in the Sovereign to one which only extends to comparatively limited rights of administrative interference. In their opinion there is no evidence that this kind of usufructuary title of the community was disturbed in law, either when the Benin Kings conquered Lagos or when the Cession to the British Crown took place in 1861. The general words used in the Treaty of Cession are not in themselves to be construe4 as extinguishing subject rights. The original native right was a communal right, and it must be presumed to have continued to exist unless the contrary is established by the context or circumstances. There is, in their Lordships' opinion, no evidence which points to is having been at any time seriously disturbed or even questioned. Under these conditions they are unable to take the view adopted by the Chief Justice and the Full Court.

Nor do their Lordships think that there has been made out any distinction between" stool" and communal lands, which affects the principle to be applied in estimating the basis on which compensation must be made. The Crown is under no obligation to pay anyone for unoccupied lands as defined. It will have to pay the Chief for family lands to which he is individually entitled when taken. There may be other portions of the land under his control which he has validly allotted to strangers or possibly even to members of his own clan or community. If he is properly deriving tribute or rent from these allotments, he will have to be compensated for the loss of it, and if the allottees have had valid titles conferred on them, they must also be compensated. Their Lordships doubt whether any really definite distinction is connoted by the expression "stool lands." It probably means little more than lands which the Chief holds in his representative or constitutional capacity, as distinguished from land which he and his own family hold individually. But in any event the point makes little difference for practical purposes. In the case of land belonging to the community, but as to which no rent or tribute is payable to the Chief, it does not appear that the latter is entitled to be compensated otherwise than in his representative capacity under the Ordinance of 1903. It is the members of his community who are in usufructuary occupation or in an equivalent position on whose behalf he is making the claim. The whole matter will have to be the subject of a proper inquiry directed to ascertaining whose the real interests are and what their values are.

source:http://www.nigeria-law.org/Amodu%20Tijani%20%20V%20%20The%20Secretary,%20Southern%20Provinces.htm